They called it the “hammer swings heard around the world.”

The hammering, in September of 1984, came from Jimmy Carter. The site was the East Village’s Mascot Flats, a six-story tenement on East 6th Street between Avenue C and D — one of many neighborhood buildings gutted in the 1970s by owners seeking insurance payouts. These landlords would load bathtubs with bricks to ensure floor collapses and guarantee their claims.

The building’s rehabilitation began when Reverend Bruce Schoonmaker of Graffiti Ministry Center on East 7th Street convinced Georgia-based Habitat for Humanity to establish its presence here in the city. He was seeking an alternative to government housing — many of his congregants were living with no heat and were being harassed by rats.

Mascot Flat’s location near Emmanuel Church, which offered its resources, made it ideal. Behind the building, in a vacant lot, an elderly woman cooked meals on a makeshift fire between cinder blocks.

Habitat purchased the roofless, gutted building from the City for $18,000 (it was appraised for $35,000), applying their “economics of Jesus” approach. The plan was to sell apartments at affordable prices to local residents who committed 1,000 work-hours to the renovation. All 370 windows were broken and without frames.

Rob DeRocker, a former Villager reporter and founding executive director of Habitat’s New York City affiliate, sparked Carter’s involvement after spotting a Daily News article in April 1984 about the ex-president planning a visit to the city in a few weeks. Carter had been involved with Habitat’s work in Haiti, so DeRocker sent the clipping to Habitat’s Georgia director, suggesting — half-seriously — that a presidential visit to Mascot Flats might boost funding.

To DeRocker’s surprise, Carter agreed.

Two weeks later, DeRocker found himself beside the former president in the back of a sedan. “There was an equanimity about him,” said DeRocker, who spoke to The Villager this week.

And there was a sense of humor. When DeRocker mentioned they were still negotiating with the city over the building’s price, Carter’s eyes twinkled. “Maybe I should call Ed Koch and suggest he increase the price,” he said. DeRocker laughed — everyone knew the mayor and the former president couldn’t stand each other. “Then he’ll give it to you for free.”

Six stories of stolen stairs

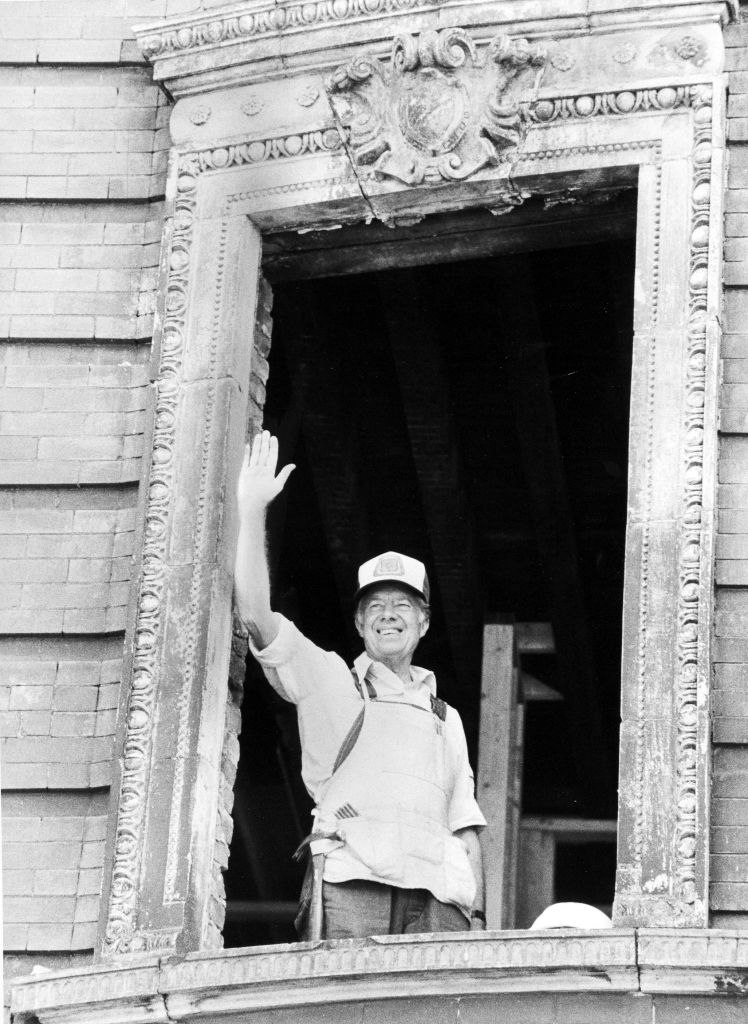

The Secret Service was uneasy about Carter climbing six stories on a temporary wooden staircase, built to replace the original marble steps stolen by drug users. From the roof, Carter viewed both Wall Street and Midtown Manhattan, and noticed the elderly woman cooking over her open fire below — an image he would reference for years.

Brian O’Donoghue, then a reporter for The Villager living on Norfolk Street, covered the visit. “For a former president to be so gracious with talking to me about his hopes and goals for this project was just really uplifting,” said O’Donoghue to The Villager this week. O’Donoghue is now a retired journalism professor in Fairbanks, Alaska.

“This is a challenge,” Carter told O’Donoghue, but called it a “good test in a major metropolitan area” of a program which is already providing “one home per day” in other parts of the world.

As Carter prepared to leave, he turned to DeRocker and said, “Rob, if there’s anything I can do to help you here, just let me know.”

DeRocker, seizing the moment, blurted out, “Thank you, Mr. President. Maybe you can send some volunteer carpenters up from your church.”

“We’ll think about it,” Carter replied. The next day, DeRocker received an unexpected call: not only had Carter agreed to send carpenters – he would be one of them.

By September, Carter was back in the East Village for a week-long work party, staying in a Hell’s Kitchen church dormitory. He became a familiar sight in the neighborhood as the press gathered daily. One day, he took the F train from Times Square to Second Avenue, another day he jogged down from Hell’s Kitchen with his Secret Service detail and DeRocker. “That was quite a site,” said DeRocker, who lived on East 12th Street and Avenue B. The work crew, including Carter, made their way to Katz’s Delicatessen, where his photo in a Habitat shirt still hangs today.

“He was very intent on doing the work in that building,” DeRocker noted. “It’s not like he was there politicking in any way. He recognized, obviously, what the visibility could do for Habitat. But he really wanted to do the work.”

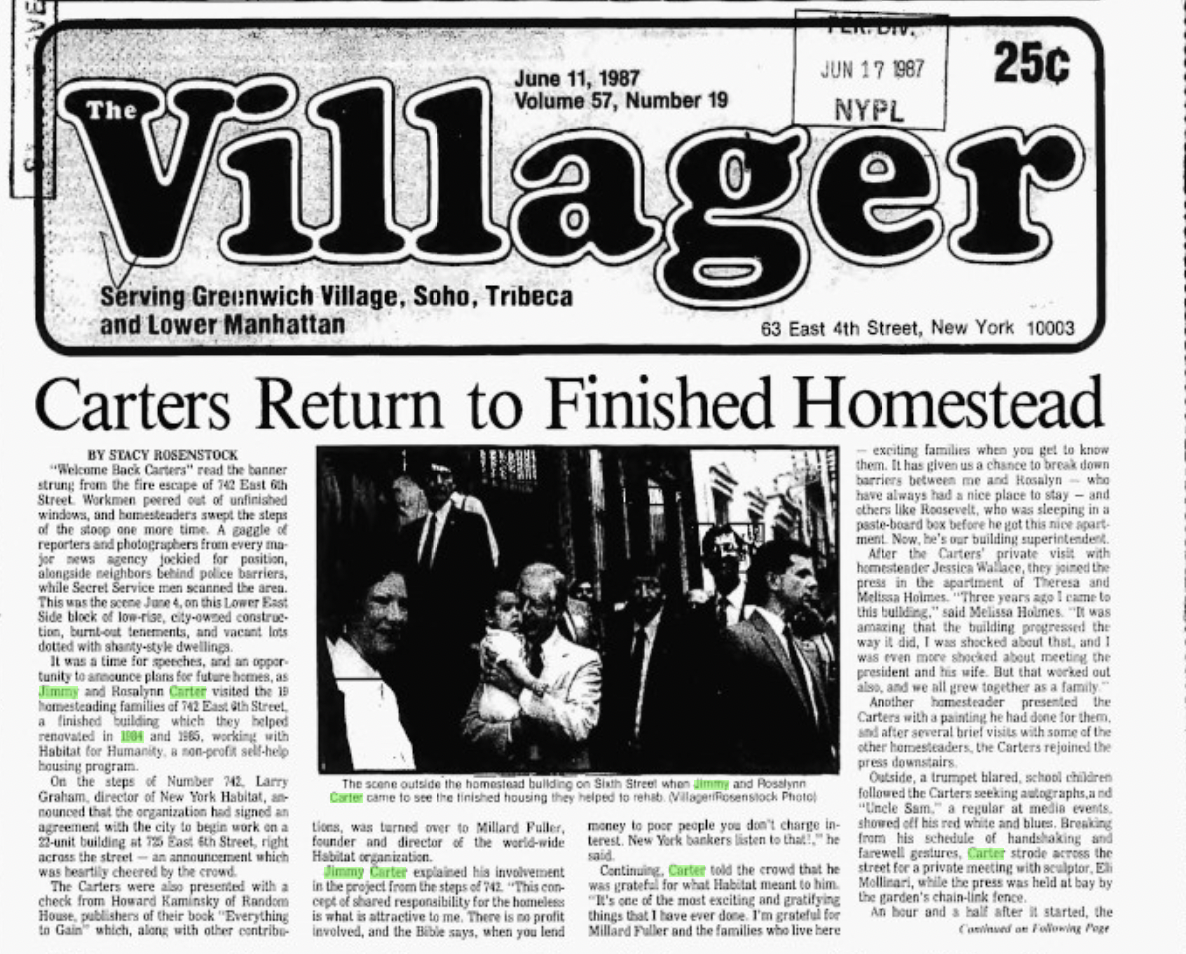

Three years after renovations began, in November 1986, 19 families moved into the rehabilitated building. It became an HDFC affordable housing cooperative. Some original “homesteaders” still reside there. The project’s success launched Habitat’s expansion – now operating in over 70 countries. In New York City, Habitat has built or restored more than 1,000 homes since Carter’s visit.

DeRocker, who went on to work in economic development marketing, reflects on the experience spiritually: “When I question whether God exists or whether he exists but just doesn’t care, I look back at that experience. What are the odds of picking up a Daily News — which I had never picked up before, and never read — and seeing that notice about President Carter’s visit and all that followed from that. To me, there’s a design. There’s just been too many coincidences to regard them as weird coincidences. You can’t write that script.”